At first glance, the education situation in Montgomery County appears better than in many of the surrounding areas. But better isn’t good enough. Countywide, education in Montgomery County is strong. Still, despite having the best graduation rate in the region and exceeding state averages on the PSSAs, there is a great divide among school districts in the county. The instructional spending gap between the highest and lowest spending districts is $142,000 per classroom. The county contains the Lower Merion School District, one of the wealthiest districts in the state, if not the nation. Montgomery County also has rising poverty—the number of students eligible for free and reduced price lunch jumped 45% from 2008 to 2012, the largest increase in the region. Chronic underfunding due to the lack of a funding formula from the state, to the tune of $34 million this year alone, has led districts across the county to raise taxes during the recession, increasing the burden on already hurting Pennsylvania families.

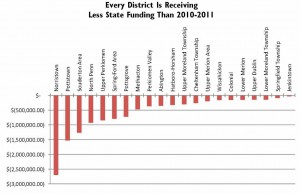

Pennsylvania is one of just three states without a funding formula for education. PCCY’s analysis has found that if the formula from 2008 remained in place, Montgomery County schools would have an additional $34 million this year from the state. But this isn’t a one-year problem. In fact, every district in the county is receiving less than it did three years ago. As you can see by the graph below, Norristown took by far the biggest funding hit, which is particularly troubling because the Norristown School District is home to the highest number of students receiving free or reduced price lunch in the county.

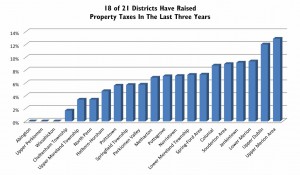

To cope with the state’s underfunding, school districts only have a few options. The money for educating students has to come from somewhere, and because layoffs are always a last resort, local taxes often have to be raised. Eighty three percent of Montco school districts have done just that since 2010 and the spending gap between districts has grown. Wealthier districts, by definition, do not need to greatly increase their tax burden to raise sufficient funds for their schools. At the other end of the spectrum, districts with weaker tax bases need to raise property taxes at a much higher rate to see even a moderate funding increase—that reality is even more troubling when you consider that the tax burden in these areas is already disproportionately high.

This economic disparity is a double whammy, hitting children in the classroom and parents in the bank account. The Pottstown School District has the highest property tax rates in the county, roughly double those in wealthy Lower Merion, but it has some of the lowest classroom spending—Lower Merion’s is about 60% higher. Lower Merion’s more than $16,000 per student instructional spending is 79% that of the lowest spending district, Upper Perkiomen. Because of this disparity, things aren’t as good as they initially seem in Montgomery County. And until there is a fair funding formula that shifts the burden from an unequal tax base, they won’t be.